PÍLDORA N. 12 | OCTUBRE DE 2023

Echos from a fading past: musical bows and umngqokolo

Bernhard Bleibinger

Investigador Científico (IMF-CSIC)

PÍLDORA N. 12 | OCTUBRE DE 2023

VITAMINA H

(Humanidades)

Echos from a fading past: musical bows and umngqokolo

Bernhard Bleibinger

Investigador Científico (IMF-CSIC)

From left to right: Nontwazana with umrhubhe mouth bow, Nowhi and Pheliwe Zatu with uhadi musical bow. June 2020. Photo by Bernhard Bleibinger.

It was in the morning of the 6th of June 2020 when we met in Khayalethu (also known as Auckland), a little village next to the street to Hogsback, approximately 30 Km north of the town of Alice in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. The meeting with Pheliwe Zatu (then 59 years old) and her two sisters Nontwazana (64 years) and Nowhi (72 years) was arranged in order to film the three sisters singing and talking of the olden days. On that day they narrated how, as young girls, they were almost forced into marriage, but managed to escape or that Pheliwe had the “calling of the ancestors” to become a traditional healer, but could not afford to undergo the training because of her children, and that singing and dancing helped her to get over the calling. They remembered their mother singing and playing musical bows and in between their stories they sang, played and danced. Almost like a side note one of them mentioned that they used to practice the umngqokolo when they were young. Umngqokolo is a very particular way of singing in the Eastern Cape which may aim at producing overtones, i.e. a second melody over fundamental tones.

We are running out of time, if we still want to conserve this precious intangible cultural heritage of the world

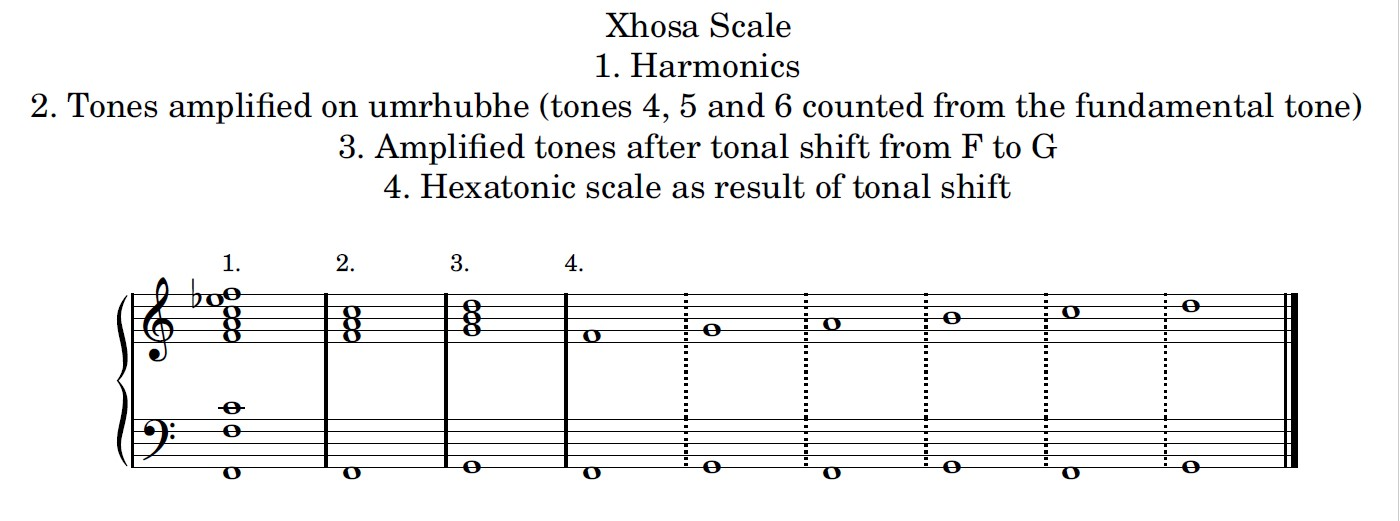

And in fact, Nowhi started a song and for a moment one could clearly hear a fifth over the fundamental tones before —due to her age, as she explained— she stopped amplifying the overtones. In this case it was the ordinary umngqokolo or umngqokolo nje, as Dave Dargie, a famous specialist for the music of the amaXhosa, would call it. Another very rare type of overtone singing in that region, the umngqokolo ngomqangi, is related with bow music, specifically that of the umrhubhe mouth bow.[1] Umrhubhe music in the Eastern Cape uses two fundamental tones (one whole tone apart) over which specific overtones are amplified in order to produce melodies based on the so-called Xhosa scale (see figure). When counting the tones upwards starting with the fundamental tone, the most important amplified tones would be the tones 4, 5 and 6. That means, if the fundamental tone is F the amplified tones would be F, A and C. A tonal shift of one whole tone (to G) —which is achieved by shortening the string by using the left thumb— leads to the tones G, B and D. Via this tonal shift a hexatonic scale (F-G-A-B-C-D) can be produced on the instrument.

The term umngqokolo ngomqangi is a reference to the musical bow umrhubhe which can also be called umqangi. Umngqokolo ngomqangi could therefore be translated like “umngqokolo in the style of the umqangi”. Nowayilethi Mbizweni from Ngqoko used the term. She was one of Dargie’s most important contacts. But, as Dargie once explained to me, she might have had something different in mind: “She thought the term came from the cicadas which the boys would impale on a thorn. The poor cicada would try desperately to escape, and produce a high buzzing sound in the process. A boy would then hold the insect before his open mouth, and resonate overtones as when playing a mouth-bow. The unfortunate cicada would then be described as umqangi. However, the way Nowayilethi sang was almost clearly related to umrhubhe (alias umqangi alias umqunge plus plus), the defining factor being the use of two fundamentals a whole tone apart, as with playing the mouth-bow.” (Email, 14 June 2023)

Production of the hexatonic Xhosa Scale on the umrhubhe mouth bow. Figure by Bernhard Bleibinger.

Even though Pheliwe and her sisters did not perform the umngqokolo ngomqangi during our meeting, all of them made overtone music: one of them performed the ordinary umngqokolo nje and the other two played the umrhubhe and uhadi [2] bows which also amplify overtones — just as they used to do it when they were young girls.

What makes that moment with umngqokolo so special is the history attached to this kind of singing: It was at the beginning of the 1980s when the before-mentioned Dave Dargie discovered this unique singing technique in Ngqoko, a village in the region of the former Transkei in the Eastern Cape Province (approximately 50 Km east-north-east from Queenstown and 160 Km north of the place where I made my recording in 2020).

At that time Dargie was working at the Lumko institute, which was part of a Catholic Mission next to Ngqoko. At Lumko he was responsible for the introduction of indigenous music in the Roman Catholic liturgy (Dargie, 2016; Bleibinger, 2019) and because of his working situation he was familiar with the music of the amaXhosa. Yet this kind of overtone singing was exceptional and only seemed to be continued by women and in regions where the old traditions were still practiced, for instance, the region of the former Transkei (some of his first recordings of umngqokolo ngomqangi are available on Youtube).[3] Later he recorded a man from Auckland —the place where I recorded the three sisters— whose technique was very similar to the umngqokolo ngomqangi. Unfortunately, this man died shortly after.

The Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Source: Encyclopædia Britannica.

Encouraged by Dargie some of the ladies from Ngqoko formed a music group in the 1980s and even performed on international stages. But over the last 40 years most of the singers known to perform umngqokolo nje and umngqokolo ngomqangi have died. In order to conserve this practice Dargie published a series of CDs and DVDs on Xhosa music and tried to organise workshops in which younger people should be trained by the singers of the Ngqoko group (they even received financial support from him).[4] At the SASRIM Conference in 2013 and the ICTM Symposium on Applied Ethnomusicology in 2014 the group was invited to give concerts and workshops in order to make the academic world aware of the problem. And in 2017 a field trip was conducted in the former Transkei region to identify locations where this unique art was still to be found, to document it and to connect potential future singers with the ladies from Ngqoko.[5] Even though the field trip led to the discovery of people who practice the ordinary umngqokolo and although younger artists are getting interested again in the musical culture of the amaXhosa, it was not possible to train or form a group of younger singers. At the moment only two women are known who can still perform the umngqokolo ngomqangi. Once they have died the unique art of overtone singing in the Eastern Cape will be gone forever.

I met Pheliwe again in December 2022, for I wanted to give her copies of the recordings and photos of the above-mentioned meeting. When I was told that her two sisters had passed away I decided to discuss the matter with an old friend first, because “voices from the grave” are not always welcomed. Yet the videos and photos I forwarded to Pheliwe via our friend Dr Norma Van Niekerk[6] were much appreciated as memories of a wonderful afternoon when we talked, laughed, sang and listened to traditional music and stories. Watching those recordings brings fond memories back to life and gives hope that there still might be some old people able to practice the art of umngqokolo nje and umngqokolo ngomqangi in unexpected places. Yet it also reminds us that we are running out of time, if we still want to conserve this precious intangible cultural heritage of the world.

Dr. Norma Van Niekerk and Pheliwe Zatu, Hogsback, Back o’ the Moon, December 2022.

From left to right: Jonathan Ncozana, Bernhard Bleibinger in Mkonjana, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa 2013.

BB with kelp trumpet, South Africa 2013.

[1] In the case of the umrhubhe overtones are amplified in the mouthcavity of the player. It is an instrument which, as the three sisters toldme, used to be played by young girls above all.

[2] The uhadi uses a calabash as resonator.

[3] Dargie’s friend Tran Quang Hai made the DVD available onyoutube. Tran Quang Hai was a specialist for overtone singing andvisited South Africa twice. He died in December 2021.

[4] It was a sum of 50000 Rand he had once received for givinglectures on Xhosa music abroad. All of it was given to the singers ofthe Ngqoko Group.

[5] I organised a first exploratory research together with TsolwanaMpayipeli who had heard of singers around Ncobo village. During thisfirst research short recordings were made and meetings with theNgqoko women were discussed. Some months later we arranged ameeting of the singers we had met during our research with theladies from Ngqoko in the Ngqoko village. Dave Dargie and Prof.Tiago de Oliveira Pinto from the UNESCO Chair on TransculturalMusic Studies at the University of Music Franz Liszt in Weimar werepresent at this meeting with performances which was filmed byMariano Gonzalez.

[6] In December 2022 Dr. Norma Van Niekerk wrote to me: “Pheliwewas ecstatic when she received these photos. I was very aware thatsome African cultures don’t want to hear ‘voices from the grave’. Idiscussed it with her, and she is keen to have the recordings on amemory stick. Later today I will go & buy a memory stick and transferthe recordings to her. You made her extremely happy! Warmgreetings”. Shortly after she handed over the recordings.

REFERENCES

Bleibinger, B. (2019). “Indigene Musik im katholischen Gottesdienst. Dave Dargie, Ntsikana und das zweite Vatikanische Konzil”. In: Dominik Höink, T. B. and Clemens, L. (Eds.). Musik und Religion (=Religion und Politik, Band 20). Baden-Baden: Ergon Verlag, 163-181.

Bleibinger, B. (2021). “A Brief Introduction to Musical Bows in Southern Africa”. In: Sazi, D. (ed.). Musical Bows of Southern Africa. New York: Bloomsbury Press, 1-34.

Dargie, D. “Umngqokolo”. In: Tran Quang Hai. UMNGQOKOLO – Thembu Xhosa – OVERTONE SINGING filmed 1985-1998 in South Africa. Retrieved from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MYj-55T6Uzs [Accessed: 17-04-2023].

Dargie, D. (1988). Xhosa Music – Its techniques and Instruments, with a Collection of Songs. Cape Town & Johannesburg: David Philip.

Dargie, D. (1991). “Umngqokolo: Xhosa overtone singing”. African Music, 7(1), 33-47.

Dargie, D. (2016). “Building on Heritage, Preserving Heritage: Music Work in Southern Africa, 1976-2016”. In: Harrison, K (ed.). Applied Ethnomusicology in Institutional Policy and Practice Studies across Disciplines in the Humanities and Social Sciences 21. Helsinki: Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies, 163-188.

Dargie, D. (2020). UMNGQOKOLO – The Thembu Xhosa Overtone Singing. Handbook and recordings by: Prof. Dr Dave Dargie, Munich, Germany, for the Dave Dargie Collection at the International Library of African Music, Rhodes University, South Africa, 2009, Second Edition November 2014, third (enlarged) edition, 2020.

Encyclopædia Britannica. “Eastern Cape”. Retrieved from: https://www.britannica.com/place/Eastern-Cape-province-South-Africa [Access date: 20/06/2023]

Pequeñas píldoras de conocimiento

PARA AFRONTAR EN MEJORES CONDICIONES ALGUNOS DE LOS RETOS SOCIALES ACTUALES